By creating an account, I agree to the

Terms of service and Privacy policy

Choose your country and language:

Africa

Americas

Asia Pacific

Europe

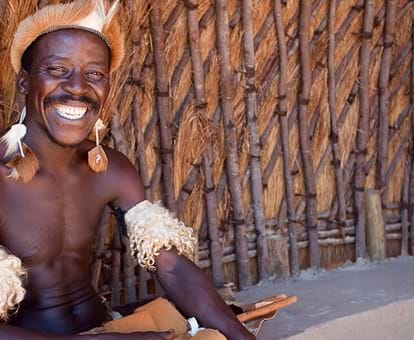

KKing Shaka kaSenzangakhona has been portrayed as a blood-thirsty dictator who ruled through coercion and instilled fear in his people. Contrary to these misrepresentations, early colonial accounts portray him as a keen international trader who went out of his way to protect the traders between 1824 and 1828.

James King, another Port Natal trader, described him as “obliging, charming, and pleasant, stern in public but good-humoured in private, benevolent, and hospitable”.

Chief Albert Luthuli, the first African Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, highlighted the cordial relationship that existed between King Shaka and the Natal traders. During the unveiling of the Shaka Memorial in September 1954, he said: “King Shaka had enthusiastically allocated land to immigrant European settlers so that they could live in peace and harmony within his kingdom and pursue their own way of life without any state interference.”

HHe promoted good neighbourliness and peace among the people of all races who resided within the kingdom and pioneered (international) trade in the area south of Delagoa Bay (Maputo). Ivory and cattle were the key items of the trade, which flourished under his guidance. As time passed, cattle ceased to be items for commercial exchange, and became important possessions for spiritual and ritual purposes, and served as material and spiritual wealth within the kingdom.

Shaka created a stratified society based on a combination of subtle socialisation and “reasonable degree” of force. At the apex were the king and aristocracy, which consisted the Zulu ruling house and the groups that were incorporated into the Zulu state during the early stages of its expansion. Closely linked to Zulu royalty and its aristocracy were the more important amakhosi (chiefs) and notables, iziphakanyiswa, who were drawn from the chiefdoms that were subjugated in the early stages of Zulu expansion. They were encouraged to align themselves politically with the established aristocracy and were made to believe that they had a shared interest in maintaining the existing social hierarchy. They were allowed to sit in the king’s ibandla (council) to discuss matters of the state.

The amaNtungwa formed the second tier and were treated as full subjects with all the rights and obligations. The aristocracy encouraged them to adopt the Ntungwa identity as a means of fostering a sense of belonging and sharing common interests and destiny with the Zulu royal family. In time, they came to think of themselves as sharing a common origin and culture. The expression: “ukuphatha njengezikhali zamaNtungwa” (handling something delicately as one would handle the weapons of the amaNtungwa) denotes the importance of this group.

The rest of the people who lived on the peripheries of the kingdom and whose subjugation was only effected in the final stages of its expansion formed part of the third tier. They were ruled less as subjects of the Zulu king than as despised outsiders. Their young were never recruited into the ranks of the amabutho (regiments). Instead, they performed menial tasks like herding cattle, and were excluded from central decision-making processes. They had fewer rights and more obligations than the members of the amaNtungwa chiefdoms. They were dismissed as amalala (the menials), the amanhlwenga (the destitutes) or iziyendane (those with strange hairstyles).

AAside from subtle social differentiation through the Ntungwa and non-Ntungwa identities, praise poetry, mobilisation of regiments (the amabutho system) and the holding of national cultural first fruit festival (umkhosi wokweshwama) were instruments of socialisation which kept the Zulu society together. Official izimbongi (praise poets) recited/or sang the reigning king’s praises (izibongo) at the amakhanda (royal barracks). This was done under normal circumstances or when the (national) army was mobilised or preparing for war. Praise poetry was fluid and varied widely depending on the whims of the poet. It became a form of official history which downplayed or downgraded anything of significance that was done by the adversaries of the king while it praised him and the royal family. Praise poetry was subsequently considered a very important cultural heritage of Zulu society.

Military conscription fostered allegiance to Shaka’s royal house while it simultaneously eroded loyalties to the other amakhosi. Only the king could mobilise troops through the regiments that were housed at the amakhanda. Only a handful of loyal and trusted amakhosi who formed part of the Zulu aristocracy could also mobilise the regiments, but with the king’s permission.

The first fruit ceremony was the key national festival through which Shaka held the nation together. It was held annually around December or January, depending on the new moon. Food, drinks, music and dance were shared and official announcements were made. He informed the attendees how the kingdom functioned and urged them to become part of it. New regiments were named, the izinduna (headmen) were appointed and the achievers awarded through the iziqu (a wooden badge). This ceremony was performed annually from 1818 to 1879.

AAbout the author

Jabulani Sithole is a former lecturer in history at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, a position he held for 13 years. He holds a Master of Arts degree in History, and is a PhD Candidate at Wits University. He co-authored a book called Zulu Identities: Being Zulu Past and Present, along with Benedict Carton and John Laband. He has served as the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Coordinator of the Liberation Heritage Route in the National Heritage Council, and former chairperson of the Albert Luthuli Museum Council. Jabulani currently writes and edits books and academic texts about Zulu history and culture.

Related articles

South Africa on social media